Written by Shaikh Ayaz

| Mumbai |

Updated: April 17, 2020 11:15:26 am

In the third essay of ‘100 Bollywood movies to watch in your lifetime’ sequence, we current 10 book-to-film diversifications to watch.

In the third essay of ‘100 Bollywood movies to watch in your lifetime’ sequence, we current 10 book-to-film diversifications to watch.

For e-book lovers, the very concept of seeing their favorite novel or work of literature flip right into a film is solely unacceptable. To the query, ‘So, how does the film compare to the book?’ the reply is often within the destructive. “The book is better,” being the usual and effectively-practiced repartee from those that prize the primacy of literature over cinema. Indeed, literature might or might not want films, however films undoubtedly want literature for its inventive development and sustenance however primarily, to entry materials that’s inaccessible in cinema. Yet, again and again, cinema has shocked lit sorts and doubting Thomases with what it will probably supply. For instance, the good director Stanley Kubrick had a knack for choosing reputed works of literature and giving them his personal twist. It’s one other matter that the authors weren’t all the time happy to see their labour of affection go up in flames within the palms of the infamous perfectionist Mr Kubrick. A query arises, then: is A Clockwork Orange the work of Anthony Burgess or of Stanley Kubrick? Does Lolita belong to Nabokov, the unique creator, or Kubrick who helped deliver the controversial novel to life on display screen? Few authors have had as a lot success in having their work tailored for display screen than John le Carré. Still, that by no means stopped the spy specialist to exclaim, “Having your book turned into a movie is like seeing your oxen turned into bouillon cubes.”

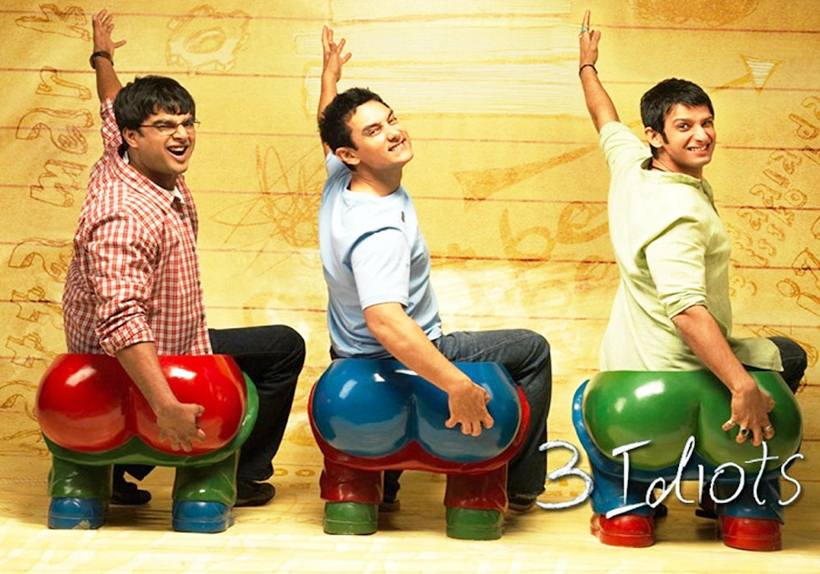

For some authors, books and flicks should not simply separate compartments of a prepare however, actually, are plying on fully totally different tracks altogether. Shall the twain ever meet? “Books and movies are different languages, and attempts at translation often fail,” Salman Rushdie had famously warned in 1999. One purpose for that pessimism might be the creator’s lengthy-held frustration to convert Midnight’s Children into a movie or TV sequence. Midnight’s Children is a prestigious winner of ‘Booker of Bookers’ and is definitely Salman Rushdie’s favorite ‘Salman Rushdie novel.’ So, when the enduring tome failed to discover takers, it plunged Rushdie into “deep depression.” After a number of false begins, a movie adaptation of Midnight’s Children (directed by Deepa Mehta) lastly took off. It was launched to tepid opinions in 2012, thus proving the grasp of magical realism proper – as an alternative of a winner, Midnight’s Children’s cinematic model was a failed try at translation. The failure merely proving that simply because you have got an awesome e-book doesn’t essentially imply it should yield an awesome movie. And the other is true simply as effectively. Sometimes, thanks to the creativeness and expertise of administrators and screenplay writers, a slipshod bestseller can lead to a extremely watchable movie. A Bollywood living proof: Raju Hirani’s three Idiots (2009), that adroitly turned Chetan Bhagat’s IIT memoir Five Point Someone right into a satire on India’s by-rote schooling system. Spearheaded by the bankable Aamir Khan, the campus comedy rewrote field-workplace historical past on its launch.

Rajkumar Hirani and Aamir Khan are champions of center-of-the-street cinema, making an attempt to merge artwork with commerce – the significant with mainstream.

Rajkumar Hirani and Aamir Khan are champions of center-of-the-street cinema, making an attempt to merge artwork with commerce – the significant with mainstream.

There is one thing literary about Aamir Khan and Raju Hirani, the dual inventive engines behind three Idiots. What’s widespread between the duo is that they’re champions of center-of-the-street cinema, making an attempt to merge artwork with commerce – the significant with mainstream, so to communicate – that predecessors like Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Gulzar, Basu Chatterjee, Guru Dutt, Vijay Anand and Nasir Hussain (Khan’s uncle) had executed so efficiently earlier than them. Hirani counts Hrishida as one among his idols and it’s straightforward to see a connection between their work. Hirani’s personal films, beginning with Munnabhai MBBS, have been likened to the Mukherjee faculty of comedies – light and middlebrow led by common stars introduced down to floor zero to channel their internal widespread man. Literature was the spine of a number of Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar hits. This can, in flip, be finest described because the Bimal Roy hangover – the unique auteur, steeped in New Theatres realism, whose finest films (Do Bigha Zamin, Parineeta, Devdas, Sujata and Bandini) drew closely from Bengali literature. Largely feminine-oriented, these classics relegated the boys to the background. Himself influenced by Italian neorealism, Bimal Roy was a mentor to each Mukherjee and Gulzar, and from him, one can guess, they might have learnt the difficult artwork of recognizing cinematic potential from the verbosity of the page. While Roy was busy conjuring up Tagore and Sharat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Gulzar added another identify to that checklist. That identify is Shakespeare. 1982’s Angoor is a uncommon mixture of Bengali and Bardish literature, leading to a madcap comedy of errors. Gulzar handed down this ardour for literature to Vishal Bhardwaj, who began out as his assistant – simply as Gulzar had joined Roy after being inspired by him to give up his job as a automobile mechanic to pursue poetry and cinema.

Today, Bhardwaj has acquired the popularity as a poster boy of Shakespearean tragedies. The Bard is the inspiration behind a few of his best films. If his cheeky take on Macbeth, Othello and Hamlet (Maqbool, Omkara and Haider respectively) is any indication, he certainly is aware of a recipe or two about how to finest translate Bard for the Hindi display screen. Shakespeare is essentially the most tailored playwright and creator on the planet. His works are strikingly related within the East and West, from Kurosawa to Orson Welles, each filmmaker price his salt has taken a crack on the Bard. But the connection that Bollywood shares with the playwright is uncommon, to say the least. Professor Jonathan Gil Harris, creator of the e-book Masala Shakespeare, has argued that the English dramatist is extra alive in Bollywood at this time than anyplace else on the planet. Harris typically jokes that Shakespeare is the “biggest screenplay writer in Hindi cinema.” In an interview with The Hindu, he stated that the Bard’s “clever use of puns and rhythm is replicated in Indian cinema. Shakespeare and Bollywood go as well together as Romeo and Juliet do.”

Besides the Bard, for a time Bollywood was captivated by the Russian and French masters. Inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Gustave Flaubert and Charlie Chaplin, administrators like Mani Kaul, Ketan Mehta and Kundan Shah tried to style the then-upcoming star referred to as Shah Rukh Khan right into a romantic and dreamy-eyed hero of their multi-fanged literary creativeness. Sanjay Leela Bhansali had in all probability wished the identical for Ranbir Kapoor, when he launched the RK inheritor in 2007’s Saawariya, a blue-canvas fable of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s White Nights.

Elsewhere, take for instance, Indian artwork cinema, you possibly can see that literature has been a powerful ally to a few of its best filmmakers. Most famously, Satyajit Ray, himself a person of letters, borrowed repeatedly from books. Ray’s solely Hindi movie, Shatranj Ke Khilari, based on Munshi Premchand’s brief fiction, is on our checklist of ‘10 Book-To-Film Adaptations to Watch.’ The social realism that Ray helped encourage in Hindi cinema paved manner to the New Wave, with administrators like Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalani on the forefront of that 1970s motion. Also referred to as parallel cinema, classics from this era resembling Ardh Satya, Tamas, Mandi and Junoon owe their existence to works of literature. Many gamers who have been a part of the 1970s scene lament that Bollywood at this time doesn’t mirror on literature as a lot because it ought to. For one, Jaya Bachchan – daughter of a Bengali author-journalist and Ray and Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s protégé – just lately recalled how her father taught her to give books as presents as a result of a “book remains on the shelf”, in contrast to candies or cookies. Bachchan went on to say that in her household as she was rising up, regional films have been seen as a cultural exercise.

That brings us to an necessary query – does Bollywood learn? And why have films stopped being a “cultural activity” they as soon as have been. While the reader is left to ponder on these questions, right here’s our checklist of ten finest Bollywood diversifications of bestsellers.

three Idiots (2009)

‘Compete or die’ – Dr. Viru Sahastrabuddhe

A nonetheless from three Idiots.

A nonetheless from three Idiots.

Rajkumar Hirani is the byword for comedy. But his flicks are equally designed as weepies of the ‘Bas kar pagle, rulayega ka kya’ selection. He is among the many new breed of latest filmmakers who’ve reset the field-workplace parameters, making Rs 100 crore sound like pocket change. Hirani’s three Idiots discovered that uncommon center floor between important acclaim and business success, a type of films that ensures a bum on each multiplex seat. Bum chairs, anybody? No pun meant! three Idiots is about three buddies from their engineering school days, however it’s actually principally about Aamir Khan who performs the novel Rancho. He has his personal manner of trying on the world, particularly the world of schooling. Diminutive and curious, he places up a hand and asks a query that the viewers is aware of will baffle the professor. He doesn’t imagine in rote studying and insists on a extra significant method that doesn’t contain parroting again a dictionary definition of issues. While different hostel-mates would queue up for his or her morning tub, Rancho showers within the park, joyously greeting lecturers and professors. All ij effectively! No surprise, Rancho is such an out of the field thinker that no person has heard from him after school. So, finest buddies Raju (Sharman Joshi) and Farhan (R Madhavan) set out to discover him. Hirani’s scathing commentary on India’s schooling system, three Idiots is riotously humorous. Special mentions for Boman Irani, a Hirani common, with a rare means to remodel into any character the director needs and Omi Vaidya as Chatur, a compulsive topper and Rancho’s bumbling foe.

Raazi (2018)

‘Chaahe jo bhi ho raha ho tumhare saath, ek nayi bahu ki muskurahat hamesha tumhare chehre pe rehni chahiye’ – Khalid Mir

Alia Bhatt in Meghna Gulzar’s Raazi.

Alia Bhatt in Meghna Gulzar’s Raazi.

Reportedly, Gulzar had expressed reservations when daughter Meghna Gulzar talked about about her intentions to flip the e-book Calling Sehmat into a movie. For Meghna, what appealed essentially the most about Calling Sehmat was that it was an intrepid younger woman’s journey. Alia Bhatt stars as that woman in Raazi. She’s no bizarre woman. She’s a spy who infiltrates Pakistan, by the act of marrying into a decent military household thus minimising all ranges of suspicion. Who would suspect this shy, tender-spoken newly married Kashmiri bride to be secretly reporting to India’s RAW? Above all, she’s performed by Alia – the final word cute-ball who, it appears, has merely scratched the floor of her expertise thus far. As informer Sehmat, Alia is spectacular each within the home scenes in addition to the coaching session and undercover ones. Jaideep Ahlawat and Vicky Kaushal put in an excellent present, matching main-girl Alia at each step. Meghna’s largest achievement in Raazi is that she manages to set the movie in a pacy thriller mode, whereas retaining her innate expertise for the best way she offers with intricacies of relationships. Here’s a delicate filmmaker who resists the narrative of us-versus-them in favour of a extra nuanced interpretation of Pakistan. She sees these throughout the border as “people.” Clues are strewn throughout Gulzar’s well timed Aye Watan that performs like an anthem in Raazi. It might have been used heroically on Sehmat to denote Indian patriotism however might serve her Pakistani husband Iqbal (Vicky Kaushal) simply as effectively.

Haider (2014)

‘Jab tak hum inteqam se azaad nahin honge na, koi azaadi humein azaad nahin kar sakti’ – Ghazala

Shahid Kapoor in a nonetheless from Haider.

Shahid Kapoor in a nonetheless from Haider.

A haunting adaptation of Bard’s Hamlet, Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider shines an unflinching gentle on the insurgency and violence in Kashmir. The firebrand Tabu performs the mothership, a posh and conflicted ‘half widow’ who practically steals the movie from her son, Haider (Shahid Kapoor). Her character Ghazala pumps a lot depth and intrigue into Haider that The New York Times reviewer wrote, “Instead of Haider, Vishal Bhardwaj might have considered calling his fast-and-loose adaptation of Hamlet ‘Ghazala’, after its Gertrude character.” Ghazala’s Oedipal relationship along with her younger son is on the core of the story – uncommon for mainstream Bollywood to skew the sacred mom-son relationship to such Freudian depths. Like in different Bhardwaj films, the music of Haider stands out for its outstanding compositions and poetry. One of the pleasures is to see Shakespeare’s gravedigger scenes became a musical romp towards the bloodstained wintery Kashmir. An ideal, if straightforward-peasy, metaphor for heaven turning into hell. In Maqbool, you would possibly recall, remodeling Macbeth’s witches into holy fools, astrology-obsessed Mumbai cops was a masterstroke of creativeness and a supply of nice humour. As a director, Bhardwaj pays shut consideration to characterisations and to the nuances of poetry and language. Watching Haider – or for that matter, any movie by him – you might be reminded again and again that it is a film made by a filmmaker who thinks like a musician.

Black Friday (2007)

‘Bombai par hamla bolenge toh international level par akkha duniya ko maloom padega, bhai’ – Tiger Memon

A nonetheless from Black Friday.

A nonetheless from Black Friday.

Based on S. Hussain Zaidi’s e-book on the Bombay blasts of 1993, one of many darkest chapters on this city sprawl of tall towers and low-mendacity shantytowns, Black Friday picks up from the place RGV’s Satya had left, so far as director Anurag Kashyap’s twin fascination for underworld and town of Mumbai is worried. Like Satya, Black Friday is a portrait of the psychology of crime. But in contrast to Satya, it doesn’t fictionalise the occasions it seeks to chronicle. The names are named. Dawood Ibrahim, for a change, isn’t hiding behind his glamorous shades. Across the border, a plot to kill Hindu leaders like Bal Thackeray and LK Advani is being brazenly mentioned. Kashyap doesn’t shy from having Tiger Memon campaign (‘jihad’) towards India’s Hindus. Memon needs to burn Bombay. Black Friday is about Tiger Memon (Pawan Malhotra) mobilising his forces, no totally different from a military main, to search revenge for the Bombay riots. Kashyap stitches the puzzle collectively by merging parts of thriller and police procedural. There’s a newsreel and documentary really feel to the film, which is deliberate and uncooked. Kashyap presents Tiger Memon (nonetheless at giant, although his brother Yakub Memon was hanged in 2015 for his position within the blast) as a person with a mission. In one scene, Memon talks in regards to the indignities confronted by Muslims, the indiscriminate rapes and killings. The blast, he maintains, is a type of revenge. It is obvious that Black Friday doesn’t want to make a hero out of Tiger Memon, although he turned one to the embittered Muslim neighborhood within the aftermath of the Bombay riots. Fair warning: The movie makes for an pressing and uncomfortable watch, given its subversively arduous-hitting topic. Kashyap had paid the worth for its realism. The movie’s launch was an ordeal for him, however it additionally made him a trigger célèbre without spending a dime speech and Bollywood’s disruptor-in-chief.

Masoom (1983)

‘Tujhse naraaz nahin zindagi, hairan hoon main’ – Gulzar

A nonetheless from Masoom.

A nonetheless from Masoom.

The most important supply of battle in Masoom is a toddler (Rahul/Jugal Hansraj) who seems solely after Shekhar Kapur has established a contented Indian household with two doting daughters (as seen by the framed household picture). When the youngsters sneak in a pet into the home, Indu (Shabana Azmi) creates a fuss, refusing to settle for him. How will she settle for her husband DK’s (Naseeruddin Shah) illegitimate little one? When it lastly dawns upon DK and Indu that Rahul is for actual now, she not solely emotionally distances herself from DK but additionally reveals anger and coldness in direction of Rahul. Both are pure responses. Kapur handles these scenes in an understated manner. For instance, when DK reveals the story behind his transient affair with Rahul’s mom in Nainital or when Rahul runs away from house after discovering who his father is. After all, think about the identification disaster of a kid, who has spent his complete life on the lookout for his lacking father. And right here’s the daddy, hesitating in uttering these reassuring phrases that might be music to Rahul’s younger years: “Yes, you are my son” The scene which will have contributed to a softening of stance happens between Indu and Chanda (Tanuja), her good friend who has simply reunited along with her household. “If I were just a woman,” Chanda says, “it would have been fine. But I am a mother, too.” Ultimately, Masoom isn’t in regards to the man or little one however in regards to the girl. Kapur offers her an opportunity at redemption in the long run. Kapur’s mature course, his means to extract stellar performances particularly within the delicate scenes between the couple when coping with troublesome questions of life and relationship and the songs by Gulzar-RD Burman which have grown to purchase a cult of their very own, betrays the director’s lack of expertise. Even although Kapur was associated to Dev-Vijay Anand (the movie, in flip, is devoted to Guru-Geeta Dutt), he was the settled company man who got here in from the blue and disrupted the established order. The apparent set off for Masoom was Erich Segal’s Man, Woman and Child. “The book made me cry,” Kapur had stated. That emotional impression impressed him to make his first movie. Overnight, the low-key debut turned this chartered accountant right into a scorching property. What a tragedy then that this nice filmmaker, because the joke goes, solely talks about films at this time as an alternative of creating one. Time to open one other e-book?

In Custody (1993)

‘Mar gayi, khatm ho gayi. Ab tum Urdu ki laash bhi dekh rahe ho. Yahan padi hai, dafn hone ke intezaar mein’ – poet Nur

Ismail Merchant directs this adaptation of Anita Desai’s marvellous novel that takes as its topic the sluggish and painful decline of not simply Urdu however a whole tradition that this language of protest and poetry helped flourish. “Who reads Urdu today,” laments writer Murad (Tinnu Anand) in an early scene. “Why should I be the torchbearer of Urdu?” he chides Deven (Om Puri), when sarcastically, Deven himself has turned to the financial comforts of Hindi. Murad is bringing out a particular version on nice Urdu poets. “Faiz, Firaq, Josh,” Murad says, lacking out on one legendary identify. “What about Janab Nur Shahjahanbadi?” Deven reminds him. “He’s dead,” counters Murad. Surely, poet Nur Shahjahanbadi is previous his prime, however no version of poetry is full with out his point out. Deven plunges into the decadent world of Nur to get him his due. Nur is a Falstaffian, alcoholic literary large performed by Shashi Kapoor, in what’s clearly his most underrated flip. Writing within the preface to Desai’s In Custody, Salman Rushdie says the movie might be Ismail Merchant’s “finest effort as a director.” Even although Rushdie complains in regards to the movie’s departure from Desai’s imaginative and prescient of the huge age hole between Deven and Nur (“the novel contrasts youth and experience”), Merchant’s model succeeds in its constancy to retaining the connection between Deven and Nur. The novel’s “emotional heart lies in this relationship,” admits Rushdie. Deploying Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s highly effective verses (be aware: Desai’s e-book begins with Wordsworth), In Custody is a requiem for Urdu poetry’s misplaced glory. Nur’s symbolic determine is a stand-in for Urdu itself. The movie posits him as a poor shadow of his former glory whereas Deven, a minor foot soldier of Urdu, finds himself turning into the true “custodian” of not simply this elegant language but additionally of Nur’s legacy and friendship.

Shatranj Ke Khilari (1977)

‘Aag lage iss khel ko’ – Khurshid

Sanjeev Kumar and Saeed Jaffrey in Shatranj Ke Khilari. (Express archive picture)

Sanjeev Kumar and Saeed Jaffrey in Shatranj Ke Khilari. (Express archive picture)

Chess is the ‘other woman’ in begum Khurshid’s (Shabana Azmi) life. Her largest enemy that retains husband Mirza Sajjad Ali (Sanjeev Kumar), a feudal baron, away from her. As Queen Victoria’s military hatches its shrewd strikes to shut in on Awadh (Lucknow), the chess-obsessed aristocrat Mirza Sajjad Ali and his good friend Mir Roshan Ali (Saeed Jaffrey) are immersed of their sport. Their adventures to discover methods to get again to the board, together with touchdown up at a good friend’s mansion as he lays on his demise mattress, offers Shatranj Ki Khilari its irony and humour. “What a lovely day, and we are bereft of chess,” Mir Roshan Ali sighs on one nice chess-much less day, as if lacking an outdated flame. As the good character actor David (taking part in Munshi Nandlal) explains, chess was invented in India, however the English made some essential modifications to its guidelines. Result? The sport’s tempo is quickened and it will get over quicker. “Do the English find our game slow,” says Mirza Sajjad Ali, visibly offended. “They find our transport slow, too,” Mir Roshan Ali butts in, referring to the arrival of trains. This is a time of nice tumult for Awadh, however Mirza and Mir’s pleasant banter and singular obsession with carrying on with their sport belies the change of guard that’s imminent. Satyajit Ray makes use of chess as a metaphor for the wily British ways. Alongside Mirza and Mir, Ray expertly levels a parallel subplot of Wajid Ali Shah, ruler of Awadh, an awesome patron of artwork and himself an ready poet and musician. How did the ruler of Awadh turn into a subplot in his personal life’s plot? A religious Muslim, he loves to costume up as Krishna and dance together with his courtesans. The catholic British discover his debauchery disgusting. One of one of the best moments within the movie happens when Awadh’s Prime Minister, bearing unhealthy information, comes crying to Wajid Ali Shah, interrupting the king’s thumri session. “Only love and poetry can bring tears to a man’s eyes,” says Wajid Ali Shah, who’s performed by the overtly masculine Amjad Khan. And that’s one other extraordinary achievement of the movie – its casting, not simply of towards-kind Amjad however of Sanjeev Kumar, Saeed Jaffrey and Tom Alter, the gora sahib who aptly turns into the bridge between English and Urdu. This is Ray’s first Hindi movie. He doesn’t know Urdu, however like all nice filmmakers, he’s alive to the cultural and political intricacies of language. Based on a Premchand brief story, Shatranj Ke Khilari is a lovingly crafted vignette from Awadh, on the eve of its annexation. The movie is without delay a paean to the bygone Awadhi and Nawabi tradition of tehzeeb and an examination of it, gently implicating the Nawabs for being answerable for their very own downfall. “We get so helpless without servants,” says Mir Roshan Ali, in direction of the tip. When insulted, he does increase the gun however not towards the British. Poetry, shisha and kebabs are all it takes for the Nawab to quiet down and resume his sport, at the same time as Queen Victoria marches in. Checkmate!

Satyakam (1969)

‘Sach bolne waale mein agar dukh sahne ki himmat hai, toh dukh dene ki bhi himmat honi chahiye. Sacchai ek angraarey ki tarah hai, haath pe rako aur haath na jale yeh kaise ho sakta hai’ – engineer Satyapriya

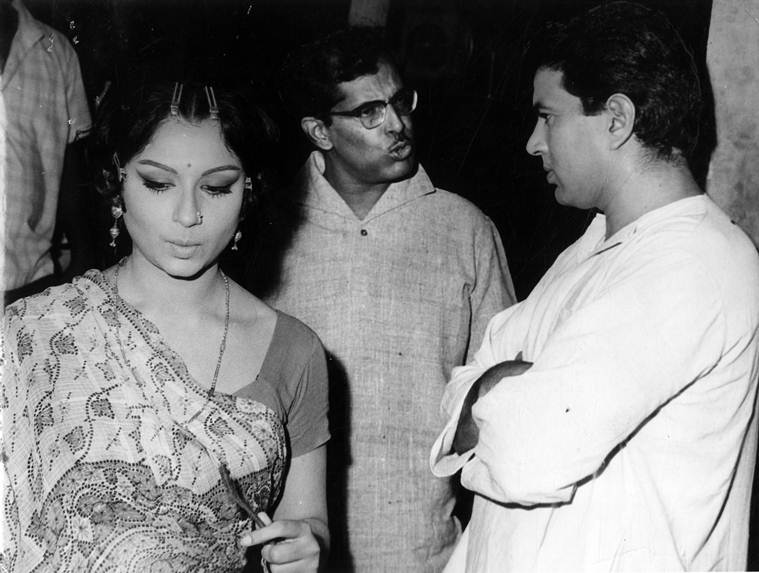

Sharmila Tagore, Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Dharmendra on the set of Satyakam. (Express archive picture)

Sharmila Tagore, Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Dharmendra on the set of Satyakam. (Express archive picture)

Those traces are uttered by Satyakam’s protagonist, the idealist Satyapriya. He’s the movie’s conscience-keeper and reality-seeker, who’s single-mindedly obsessive about doing the appropriate factor, no matter the fee. The story of Satyakam is narrated by Naren (Sanjeev Kumar). Hrishikesh Mukherjee would use this storytelling system later on in Anand (1971), the place a strapping Amitabh Bachchan recollects the weird lifetime of Anand, performed memorably by Rajesh Khanna. Satyapriya (Dharmendra) and Naren are school buddies in pre-Independence India. After school, they go separate methods, remaining off and on in contact. For some years, Satyapriya hasn’t written to Naren. When they stumble upon one another in the future, Satyapriya fills within the lacking items. He had to marry dance woman Ranjana (Sharmila Tagore). She has a toddler that Satyapriya accepts to increase as his personal. And but, Ranjana typically feels she’s “impure” and needs to be reborn “pure” to be worthy of Satyapriya. Reworking Narayan Sanyal’s novel, Mukherjee’s Satyakam is in regards to the seek for reality and to commit to its wholeheartedly. This is Satypriya’s solely function in life and he has on condition that that means to himself, in contrast to Naren, who in an early school scene discussing an existential query, appears to come throughout as a nihilist believing within the utter meaninglessness of life. Dharmendra performs Satyapriya with an unmistakable sincerity and understatement that delicate Bengali administrators like Mukherjee and Bimal Roy recognized within the younger Jat. (Note that Dharmendra had already turn into a serious star with Phool Aur Patthar in 1966.) Hrishida spent the 1970s replicating the identical mannequin with business stars like Rajesh Khanna and Amitabh Bachchan.

Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962)

‘Swami ke liye hi aurat ka jeevan hai’ – Chhoti Bahu

A nonetheless from Sahib, Bibi Aur Ghulam.

A nonetheless from Sahib, Bibi Aur Ghulam.

‘Chand ma daag hai, par unma daag naahin,’ (‘The moon has spots, but not her,’),” that’s how a trustworthy servant of Chaudhary clan describes the haveli’s enigmatic Chhoti Bahu. In the movie’s opening, we meet the gauche Bhootnath (Guru Dutt) and Jaba (a sprightly Waheeda Rehman). But director Abrar Alvi (tales abound of Dutt’s ghost course) waits earlier than introducing the storied Chhoti Bahu. Meena Kumari performs her with arresting pressure, carrying music in her voice and painful longing in her eyes. This efficiency was instrumental in constructing the Meena Kumari cult. We first see her when Bhootnath sees her. “Aao, idhar aao,” says Chhoti Bahu imploring a reticent Bhootnath, nearly in a maternal manner. (Years later, the identical magnetic voice would act as a pacifier between warring buddies in Gulzar’s Mere Apne). She’s the one one who finds the identify Bhootnath stunning. Not certain if the grande dame of tragedy is joking or critically means it. But the poor Bhootnath’s response is one among utter shock. Now, should you ignore frumpy names like Bhootnath and Jaba (“Was there ever such an ugly name?” writes Jerry Pinto in an essay on Waheeda Rehman), there’s loads of pleasures on this 1962 adaptation of Bimal Mitra’s Bengali novel. Chhoti Bahu’s loveless marriage sends her into boozy decline. All she yearned for was love and sexual fulfilment from her husband (Rehman). But that is Meena Kumari. Suffering, pining and sorrows are her birthright and she or he has it, not less than in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam – her best sob story and a cultural touchstone, to boot.

100 Bollywood films to watch in your lifetime sequence | 10 socially related films from Bollywood | 10 important Hindi crime thrillers.

Devdas (1955)

‘Kaun kambakht hai jo bardasht karne ke liye peeta hai’ – Devdas

Suchitra Sen and Dilip Kumar in Devdas. (Express archive picture)

Suchitra Sen and Dilip Kumar in Devdas. (Express archive picture)

Judging purely by the variety of diversifications it has impressed, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas is by far Bollywood’s go-to work of literature. It has been remade a number of instances. Filmmakers as numerous as Sanjay Leela Bhansali, Sudhir Mishra and Anurag Kashyap have put their very own spin on the tragic story. Yet, it’s Bimal Roy’s 1955 reboot starring Dilip Kumar, Vyjayanthimala, Suchitra Sen and Motilal that has a declare to being one of the best Devdas. What makes it so nice? The story is similar outdated chestnut. But in 1955, it may not have been such a cliche. A meek younger man, Devdas (Kumar) is torn between Paro (Sen) and Chandramukhi (Vyjayanthimala). Craving for love, he takes to the bottle. For Kumar, it is a justly celebrated efficiency, in all probability a excessive level not only for this movie but additionally for his profession. His character stands for resignation and defeat. When he can’t rise up to his family for his childhood love, how can he ever face the world? Vyjayanthimala, who made for a preferred display screen couple with Kumar, performs the courtesan whose kindness Devdas guarantees by no means to neglect. But does he love her? He solely really loves Paro. In the movie’s famously tragic climax, she runs to get a final glimpse of Devdas. Alas, it’s too late.

(Shaikh Ayaz is a author and journalist based in Mumbai)

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click right here to be part of our channel (@indianexpress) and keep up to date with the newest headlines

For all the newest Entertainment News, obtain Indian Express App.

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd