Written by Amaal Akhtar | New Delhi |

Updated: July 11, 2020 four:38:23 pm

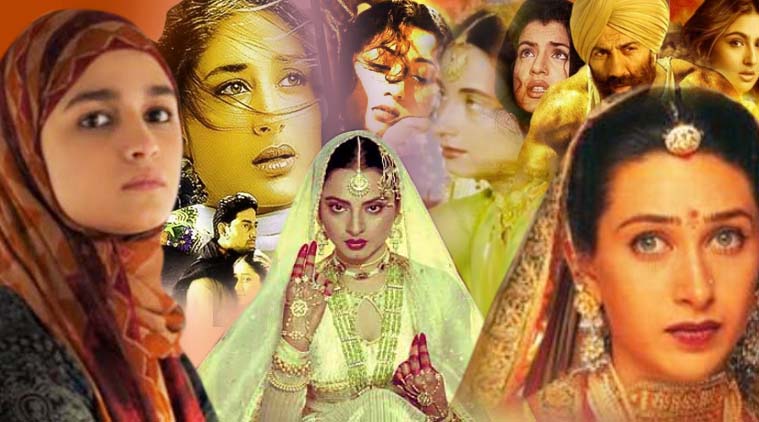

In his e-book The Ugliness of the Indian Male, Mukul Kesavan observes that Muslim women have suffered the ‘double handicap of gender and community’ in Hindi cinema.

In his e-book The Ugliness of the Indian Male, Mukul Kesavan observes that Muslim women have suffered the ‘double handicap of gender and community’ in Hindi cinema.

It is telling that within the historical past of Hindi movies, if one casts a cursory look again, solely a valuable few Muslim women characters come to thoughts. Most memorable are tragic tawaifs from classics like Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and Pakeezah (1972), embodying the romanticised ultimate of erstwhile nawabi gentility. Relegated to margins of society, their tales have been concerning the craving for respectability, at all times sought in a person’s love and the domesticity of marriage. The private strife of the actresses added poignance, since movie appearing for women was equally stigmatised because the area of ‘loose women’. The eighties, giving us the style-defining Umrao Jaan (1981) and extra by-product fare like Tawaif (1985), in the end signaled the courtesan’s swansong.

Most memorable Muslim women characters from the 60s and 70s are tragic tawaifs from classics like Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and Pakeezah (1972), embodying the romanticised ultimate of erstwhile nawabi gentility. (Source: Youtube display screen seize)

Most memorable Muslim women characters from the 60s and 70s are tragic tawaifs from classics like Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and Pakeezah (1972), embodying the romanticised ultimate of erstwhile nawabi gentility. (Source: Youtube display screen seize)

During the eighties, Shah Bano’s excessive-profile authorized battle pushed debates on minority spiritual practices versus gender justice into public discourse. This prompted the ‘Muslim woman’ to be pulled from yesteryear nostalgia into modern realities in Hindi movies. In Coolie (1983), the last decade additionally noticed a uncommon Muslim everyman hero, however the identical defiant spirit didn’t prolong to Muslim women, who remained soaked in victimhood. With Nikaah’s (1982) indictment of triple-talaq got here an early signposting of Hindi cinema’s preoccupation with saving Muslim women from a range of crises, which normally concerned the regressive and violent tendencies of Muslim males.

With Nikaah’s (1982) indictment of triple-talaq got here an early signposting of Hindi cinema’s preoccupation with saving Muslim women from a range of crises. (Source: Youtube display screen seize)

With Nikaah’s (1982) indictment of triple-talaq got here an early signposting of Hindi cinema’s preoccupation with saving Muslim women from a range of crises. (Source: Youtube display screen seize)

In the 1990s, amidst a surge of communalism, Hindi movies explored a legal underworld is proportionally populated by Muslim males and the place Muslim women have been both absent, inconsequential, or disposable. When they did seem in focus, as in Henna (1991), Bombay (1995), Mission Kashmir (2000), cross-border tensions grew to become a precondition for his or her mere presence. If Muslim, they might additionally normally be Pakistani, in a neat overlapping of faith with nationality, with Kashmir as a 3rd recurring axis. Khaled Mohamed’s Mammo (1994), Fiza (2000) and Zubeidaa (2001) symbolise a pointed departure for his or her delicate and regarded illustration of a cross-part of Muslim women, and so they finest encapsulate the transition from the nineties to the aughts.

By the 2000s, these representations had a worldwide context the place 9/11 was a turning level that made the ‘Muslim terrorist’ a pop-cultural mainstay. Muslim males grew to become public enemies, embodying evils of Islamic fundamentalism, each actual and perceived. These overwhelmingly unfavourable depictions stay potent in Western, particularly British and American, leisure to today. Here, Muslim women seem as both ruthless co-conspirators or hapless brutalised victims of Muslim males (Homeland, Bodyguard and Jack Ryan). They are solely noble when aiding the white American heroes, however in both case, they perish as collateral injury. Anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod has highlighted Western media’s concern with ‘saving’ Muslim women as a self-serving white-saviour complicated which sidesteps the American state’s implication in enabling oppressive regimes.

Post-9/11 Islamophobia solely compounded present communal fault-traces and the saviour-complicated displayed its personal pressure in Hindi movies. At the daybreak of the millennium, Muslim women in movies like Refugee (2000) and Gadar (2001) have been much less totally-realised characters than heavy-handed allegories concerning the trauma and futility of conflict. Gadar depicted a Pakistani Muslim lady being saved by a valiant Sikh man within the context of post-Partition communal riots. The movie was awash with stereotypes, however whereas Sikh bravery was positively bolstered, the narrative of Muslims as betrayers and riot-instigators was set in stone, to be repeated in latest movies like Kalank (2019).

At the daybreak of the millennium, Muslim women in movies like Refugee (2000) and Gadar (2001) have been much less totally-realised characters than heavy-handed allegories concerning the trauma and futility of conflict. (Source: YouTube display screen seize)

At the daybreak of the millennium, Muslim women in movies like Refugee (2000) and Gadar (2001) have been much less totally-realised characters than heavy-handed allegories concerning the trauma and futility of conflict. (Source: YouTube display screen seize)

The 2000s additionally popularised the visually spectacular historic epics in Hindi cinema, and these have been one other pure habitat for Muslims. Jodhaa Akbar (2008) considered its eponymous Muslim emperor with a delicate heroic lens, giving a muted dignity to his relationship with the Hindu queen. Taking the mantle of ostentatious interval dramas ahead within the 2010s, two Sanjay Leela Bhansali movies provide a case-examine within the cultural and sexual politics of interreligious romance. In Padmaavat (2018), a Muslim emperor is a sexually deviant beast whose attraction to a lovely Hindu queen is just repulsive. However, in Bajirao Mastani (2015), as a Hindu king is enraptured by a Muslim warrior-princess, the last word forbidden fruit, the movie works exhausting to raise adultery to timeless ‘true love’. This distinction between love and lust is even acknowledged in a dramatic declaration: ‘Bajirao ne Mastani se mohabbat ki hai, aiyashi nahi’. Even in additional temperate tales of interreligious love like Veer Zaara (2004), the villainous obstacles are the Pakistani woman’s orthodox Muslim household. In different phrases, the creativeness of interreligious romance in Hindi movie has fixated on Hindu-Muslim couplings, revealing thinly-veiled anxieties about each faith and gender.

The 2000s additionally popularised the visually spectacular historic epics in Hindi cinema, and these have been one other pure habitat for Muslims. Jodhaa Akbar (2008) considered its eponymous Muslim emperor with a delicate heroic lens, giving a muted dignity to his relationship with the Hindu queen. Taking the mantle of ostentatious interval dramas ahead within the 2010s, two Sanjay Leela Bhansali movies provide a case-examine within the cultural and sexual politics of interreligious romance. In Padmaavat (2018), a Muslim emperor is a sexually deviant beast whose attraction to a lovely Hindu queen is just repulsive. However, in Bajirao Mastani (2015), as a Hindu king is enraptured by a Muslim warrior-princess, the last word forbidden fruit, the movie works exhausting to raise adultery to timeless ‘true love’. This distinction between love and lust is even acknowledged in a dramatic declaration: ‘Bajirao ne Mastani se mohabbat ki hai, aiyashi nahi’. Even in additional temperate tales of interreligious love like Veer Zaara (2004), the villainous obstacles are the Pakistani woman’s orthodox Muslim household. In different phrases, the creativeness of interreligious romance in Hindi movie has fixated on Hindu-Muslim couplings, revealing thinly-veiled anxieties about each faith and gender.

In the final decade, three Idiots (2009) and Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011) marked perceptible shifts by having Muslim males inhabit slice-of-life tales the place their faith is incidental however not minimised. For Muslim women, such parallels are more durable to search out. They have tended to be benign creatures, exceedingly weak and sometimes exoticised. In Saawariya (2007), she exists in literal shadows, barely speaks, and is tethered to her grandmother with a hairpin. In the healthful household dramas, they’re older women in literal service of Hindu protagonists as caretakers and matrons, like Rifat Bi in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1999) and Daijaan in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001). In Bajrangi Bhaijan (2015), she is a Pakistani baby, made much more helpless by her listening to impairment. Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016) held promise for depicting two rich and self-possessed Muslim women as main characters, however the movie’s subversive potential can’t be overstated. In Karan Johar’s cinema, solely class manifests itself and all different identities are decorative. When the movie grew to become embroiled in a political controversy, it was re-edited and the feminine protagonist’s hometown modified from Karachi to Lucknow. This retrospective correction begs the query, why couldn’t she be Indian Muslim within the first place? Why have Hindi filmmakers discovered it tough to envisage the occasional Muslim lady they write as each Muslim and Indian?

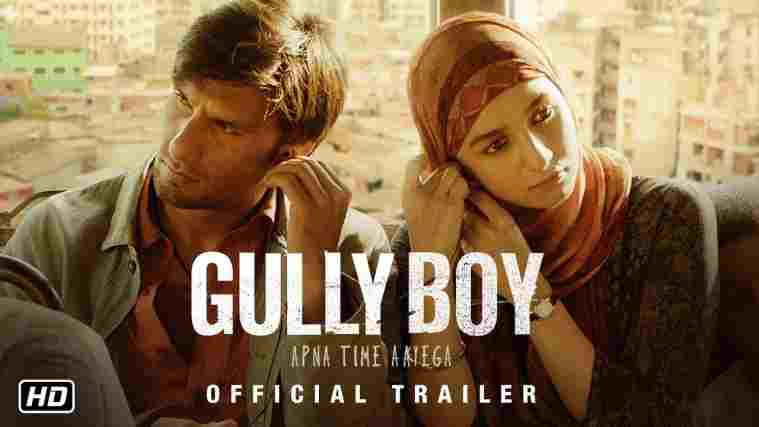

In the final twenty years, reconciling these identities has, for each Muslim males and women, concerned more and more greater stakes, the place they’re required to always show their loyalty, patriotism, and ‘not-terrorist’-ness. My Name Is Khan (2010) epitomised this problematic publish-9/11 expectation positioned on Muslim males and extra just lately, movies like Raazi (2018) have recruited Muslim women as spies to related impact, albeit displaying extra nuance on themes of nationalism. Given Hindi cinema’s checkered historical past of Muslim illustration, it’s no marvel that Gully Boy (2019) got here as a aid and struck a chord. In Safeena’s ordinariness younger Muslim women discovered validation of their a number of identities and their want to be authentically represented as folks with temperaments, goals, company and ambitions, which has been missing in Hindi movies. In his e-book The Ugliness of the Indian Male, Mukul Kesavan observes that Muslim women have suffered the ‘double handicap of gender and community’ in Hindi cinema. This might effectively be referring to the lived experiences of quite a few Muslim women in India, however Hindi movies have largely chosen to be patronising and alienating of their depictions.

Given Hindi cinema’s checkered historical past of Muslim illustration, it’s no marvel that Gully Boy (2019) got here as a aid and struck a chord. (Source: Youtube screengrab)

Given Hindi cinema’s checkered historical past of Muslim illustration, it’s no marvel that Gully Boy (2019) got here as a aid and struck a chord. (Source: Youtube screengrab)

We have witnessed Muslim women throughout strata making their voices heard, asserting their presence in public, and defining their very own political identification as equal Indian residents in the previous few months. Off-screen, they’ve taken cost of their tales, proving that they by no means wanted to be spoken for or rescued, however for a significant reflection of this actuality in cinema, Muslim women should write their very own tales on-display screen too.

Amaal Akhtar is a PhD analysis scholar in History at JNU, the place she additionally accomplished her MPhil. She can be a former greater-educational editor at Orient BlackSwan Pvt. Ltd.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click right here to affix our channel (@indianexpress) and keep up to date with the newest headlines

For all the newest Research News, obtain Indian Express App.